Ramsay

"centrifugal force. A third note produced by the prime 5 is derived from the note produced by the first power of 3, and this note by the first power of 5 having being slightly acted on by the force of gravity, and the first power of 5 having only a little centrifugal force, the result is that this note E in the scale of C, derived from the first power of 3 by the prime 5, is balanced between the two forces. It is the only note in the system which in the octave scale has not a large interval on the one side of it nor on the other, and consequently it is the only note which attracts and is attracted by two notes from proximity. Thus it is that the musical system is composed of three notes having specific gravity and three having specific levity or bouyancy, and one note, E, the center of the tonic chord, balanced between these two forces. As the attractions of notes from proximity take place when the notes with downward tendency meet the note with upward tendency, had the notes been animated by only one of these forces there could have been no system of resolutions of the notes either in melody or harmony; they would all have been by gravity weighing it downwards, or by levity soaring upwards." [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 28]

Getting Fifths as we ascend toward the number twelve they are in themselves the same, but with regard to their relationships they are quite different. Before and up to the twelfth fifth no scale has all the notes at the same distance above the first scale of the series. But after twelve, the thirteenth scale for example, B#, supposing the scale to be marked by sharps only, is a comma and a very small ratio above C; Cx is the same distance above D of the first scale; Dx the same above E; E# is the same distance above F; Fx the same distance above G; Gx the same distance above A; and Ax the same distance above B. So the scale of B# is just the scale of C over again at the distance of twelve-fifths, only it is a comma and the apotome minor higher; and each series of twelve-fifths is this distance higher than the preceding one. [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 30]

The major scale is composed of three fifths with their middle notes, that is to say, their thirds. And as three such fifths are two octaves, less the small minor third D to F, taking the scale of C for example, so these three fifths are not joined in a circle, but the top of the dominant and the root of the subdominant are standing apart this much, that is, this minor third, D, e, F. Had they been joined, the key would have been a motionless system, with no compound chords, and no opening for modulation into other keys. [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 38]

N.B. - The sharp comes here by the prime 5, and the comma by the prime 3. Now we have the key of G provided for;-

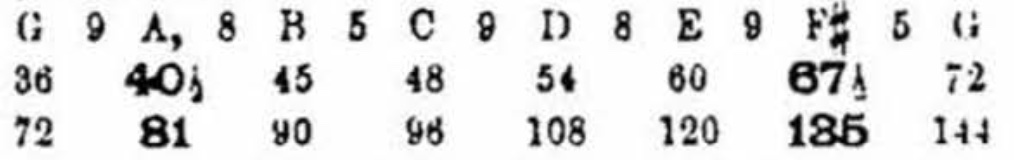

These are two octaves of the scale of G. G A B, which in the scale of C was an 8-9-comma third, must now take the place of C D E, which in C was a 9-6-comma [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 82]

third; and in order to do so, A has been mathematically raised a comma, which makes G A B now a 9-8 comma third. E F G, which in the scale of C was a 5-9 comma third, must now take the place of A B C in the scale of C, which was a 9-5 comma third; and in order to do so, F is mathematically raised 4 commas, and must be marked F#; and now the interval is right for the scale of G. E F# G is a 9-5 comma interval. This mathematical process, in the majors, puts every scale in its original form as to vibration-numbers; but since the same letters are kept for the naming of the notes, they must be marked with commas or sharps, as the case may be. In the Sol Fa notation such marks would not be necessary, as Do is always the key-note, Ray always the second, and Te always the seventh. [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 83]

Seven notes in the Octave are required for the major scale, e.g., the scale of C. All the notes of the relative minor A are the same as those of the scale of C major, with exception of D, its fourth in its Octave scale, and the root of its subdominant in its chord-scale; thus, one note, a comma lower for the D, gives the scale of A minor. [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 88]

The Plate shows the Twelve Major and Minor Scales, with the three chords of their harmony - subdominant, tonic, and dominant; the tonic chord being always the center one. The straight lines of the three squares inside the stave embrace the chords of the major scales, which are read toward the right; e.g., F, C, G - these are the roots of the three chords F A C, C E G, G B D. The tonic chord of the scale of C becomes the subdominant chord of the scale of G, etc., all round. The curved lines of the ellipse embrace the three chords of the successive scales; e.g., D, A, E - these are the roots of the three chords D F A, A C E, E G B. The tonic chord of the scale of A becomes the subdominant of the scale of E, etc., all round. The sixth scale of the Majors may be written B with 5 sharps, and then is followed by F with 6 sharps, and this by C with 7 sharps, and so on all in sharps; and in this case the twelfth key would be E with 11 sharps; but, to simplify the signature, at B we can change the writing into C, this would be followed by G with 6 flats, and then the signature dropping one flat at every new key becomes a simpler expression; and at the twelfth key, instead of E with 11 sharps we have F with only one flat. Similarly, the Minors make a change from sharps to flats; and at the twelfth key, instead of C with 11 sharps we have D with one flat. The young student, for whose help these pictorial illustrations are chiefly prepared, must observe, however, that this is only a matter of musical orthography, and does not practically affect the music itself. When he comes to the study of the mathematical scales, he will be brought in sight of the exact very small difference between this B and C?, or this F# and G?; but meanwhile there is no difference for him. [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 108]

Hughes

densed into a pair; as an example, we trace the notes and colours in the fundamental scale of C. [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, On Colours as Developed by the same Laws as Musical Harmonies3, page 20]

Notes and colours are thus condensed into a pair springing from the fountain, and mingling with each other in an endless variety. Although yellow as a colour is explained away as white, it is, nevertheless, the colour yellow in endless tints and shades throughout nature, and proves to us that the three great apparent primaries correspond to the tonic chord of the scale of C—i.e., C, E, G = red, yellow, blue; or more correctly, C and G correspond to red and blue with the central fountain of E, white and black mingled, from which all tones and colours arise. [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, On Colours as Developed by the same Laws as Musical Harmonies3, page 20]

The twelve key-notes, with the six notes of each as they veer round in trinities, are again written in musical clef, and the scales added. The key-note leads the scale, and, after striking the two next highest notes of the seven of the harmony, goes forward, with its four lowest, an octave higher. The seven of each harmony have been traced as the three lowest, thus meeting the three highest in three pairs, the fourth note being isolated. Notwithstanding the curious reversal of the three and four of the scale, the three lowest pair with the three highest, and the fourth with its octave. The four pairs are written at the end of each line, and it will be seen how exactly they all agree in their mode of development. Keys with sharps and keys with flats are all mingled in twelve successive notes. If we strike the twelve scales ascending as they follow each other, each thirteenth note being octave of the first note of the twelve that have developed, and first of the rising series, the seventh time the scales gradually rise into the higher series of seven octaves beyond the power of the instrument. Descending is ascending reversed. After the seven and octave of a scale have been sounded ascending, the ear seems to lead to the descending; but ten notes of any scale may be struck without the necessity of modulation; at the seventh note we find that the eleventh note in the progression of harmonics rises to meet the seventh. For instance, B, the seventh note in the scale of C, must have F#. This point will be fully entered into when examining the meeting of fifths. To trace the scale of C veering round as an example for all, we may begin with C in Diagram II., and go forward with F, G, A, and B an octave higher. If the twelve scales were traced veering round, they would be found to correspond with the twelve as written in musical clef. [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, Diagram IV - The Development of the Twelve Major Scales, page 26a]

In the development of the key-notes, the sharp or flat is written to each note, but not to the keys. The reversal of the three and four notes of each seven of the twelve key-notes and their trinities meeting by fifths having been traced, we will now examine the twelve scales meeting by fifths, and the results arising from the reversal of the three and four notes of each fifth lower scale in the fifth higher. Take as an example the scale of C: C D E F G A B, and that of G: G A B C D E F#. The four lowest notes of the seven of C are the four highest, an octave higher, in G; F, the central and isolated note of the seven of C, having risen a tone higher than the octave in the scale of G. The twelve scales thus modulate into each other by fifths, which sound the same harmonies as the key-notes and their trinities. Refer to the twelve scales written in musical clef ascending by fifths, and strike them, beginning at the lowest C in the bass clef; this scale sounds no intermediate tones, but these must be struck as required for all the scales to run on in fifths. After striking the seven notes of C, if we fall back three, and repeat them with the next four notes of the seven; or strike the seven and octave of C, and fall back four, repeating them and striking the next four, the four last notes of each scale will be found to be always in the harmony of the four first of the fifth higher scale. When the twelve scales ascending have been thus gained, as we trace them also on the table, they may be struck descending by following them as written in musical clef upwards, and [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, Diagram VII - The Modulating Gamut of the Twelve Keys2, page 30]

If we examine the line last quoted by the laws of life which regulate the foregoing scheme, we may compare it with the fundamental threefold chord of the scale of C and its relative colours,

| C | E | G | C red rises

|

RED. | BLUE. |

from the fountain key-note which contains in itself all tones. "Him first," the Son of God proceeding from the Almighty, and yet in Himself the Trinity in Unity. E, yellow or light. E is the root of B, ultra indigo, or black. "Him midst," the Almighty Father, the Fountain of life, light gradually rising and dispelling darkness. G, blue, "Him last," the Holy Spirit, proceeding from the Father and the Son, Trinity in Unity. The Son of God and the Holy Spirit are the complemental working pair throughout the universe; each containing "the seven spirits of life." Red and blue contain all colours in each. C and G are a complemental pair, C rising from the fountain key-note which contains in itself all tones, and C and G combine all tones in each. In Chapter III. it is explained that all varieties of tones and colours may be condensed into this pair, rising from and falling again into the fountain. [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, Reflections on the Scheme2, page 44]

See Also