Hughes

THE twelve keys have been traced following each other seven times through seven octaves, the keys mingled, the thirteenth note being the octave, and becoming first of each rising twelve. Thus developing, the seven notes of each eighth key were complementary pairs, with the seven notes of each eighth key below, and one series of the twelve keys may be traced, all meeting in succession, not mingled. When the notes not required for each of the twelve thus meeting are kept under, the eighths of the twelve all meet by fifths, and as before, in succession, each key increases by one sharp, the keys with flats following, each decreasing by one flat; after this, the octave of the first C would follow and begin a higher series. It is most interesting to trace the fourths, no longer isolated, but meeting each other, having risen through the progression of the keys to higher harmonies. In the seven of C, B is the isolated fourth, meeting F#, the isolated fourth in the key of G, and so on. Each ascending key-note becomes the root of the fifth key-note higher; thus C becomes the root of G, &c. [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, Diagram VII - The Modulating Gamut of the Twelve Keys1, page 29]

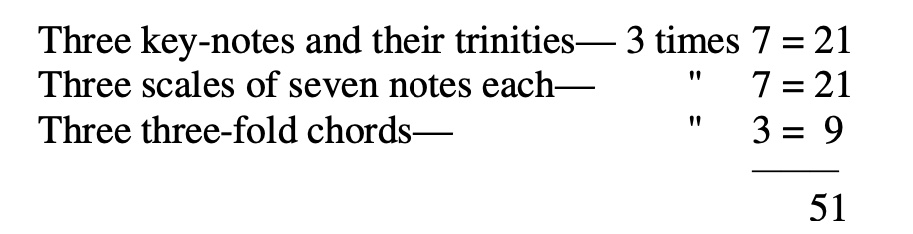

In the development of the key-notes, the sharp or flat is written to each note, but not to the keys. The reversal of the three and four notes of each seven of the twelve key-notes and their trinities meeting by fifths having been traced, we will now examine the twelve scales meeting by fifths, and the results arising from the reversal of the three and four notes of each fifth lower scale in the fifth higher. Take as an example the scale of C: C D E F G A B, and that of G: G A B C D E F#. The four lowest notes of the seven of C are the four highest, an octave higher, in G; F, the central and isolated note of the seven of C, having risen a tone higher than the octave in the scale of G. The twelve scales thus modulate into each other by fifths, which sound the same harmonies as the key-notes and their trinities. Refer to the twelve scales written in musical clef ascending by fifths, and strike them, beginning at the lowest C in the bass clef; this scale sounds no intermediate tones, but these must be struck as required for all the scales to run on in fifths. After striking the seven notes of C, if we fall back three, and repeat them with the next four notes of the seven; or strike the seven and octave of C, and fall back four, repeating them and striking the next four, the four last notes of each scale will be found to be always in the harmony of the four first of the fifth higher scale. When the twelve scales ascending have been thus gained, as we trace them also on the table, they may be struck descending by following them as written in musical clef upwards, and [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, Diagram VII - The Modulating Gamut of the Twelve Keys2, page 30]

We pass on to the developing of the minor keys. [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, The Twelve Scales Meeting by Fifths, page 31a]

If we strike the ascending scales as written in musical clef again, beginning with the lowest A in the bass clef, we see that the second and sixth notes of each scale meet in higher harmony; the sharp or flat of the scale which varies from the seven notes of its harmony is written to each note. We descend as written in musical clef upwards; each third and seventh note meet in lower harmony, and thus all exactly agree in their mode of development. Having examined the scales as written in the table below, where the sharp or flat as before is marked to each note, but not to the keys, let us strike the key-notes, trinities, scales, and chords. The three harmonies of each key are written at the end of each line of musical clef. To descend, we follow the musical clef upwards, as before. [Harmonies of Tones and Colours, Diagram XIV - The Modulating Gamut of the Twelve Minor Keys by Fifths2, page 40]

See Also