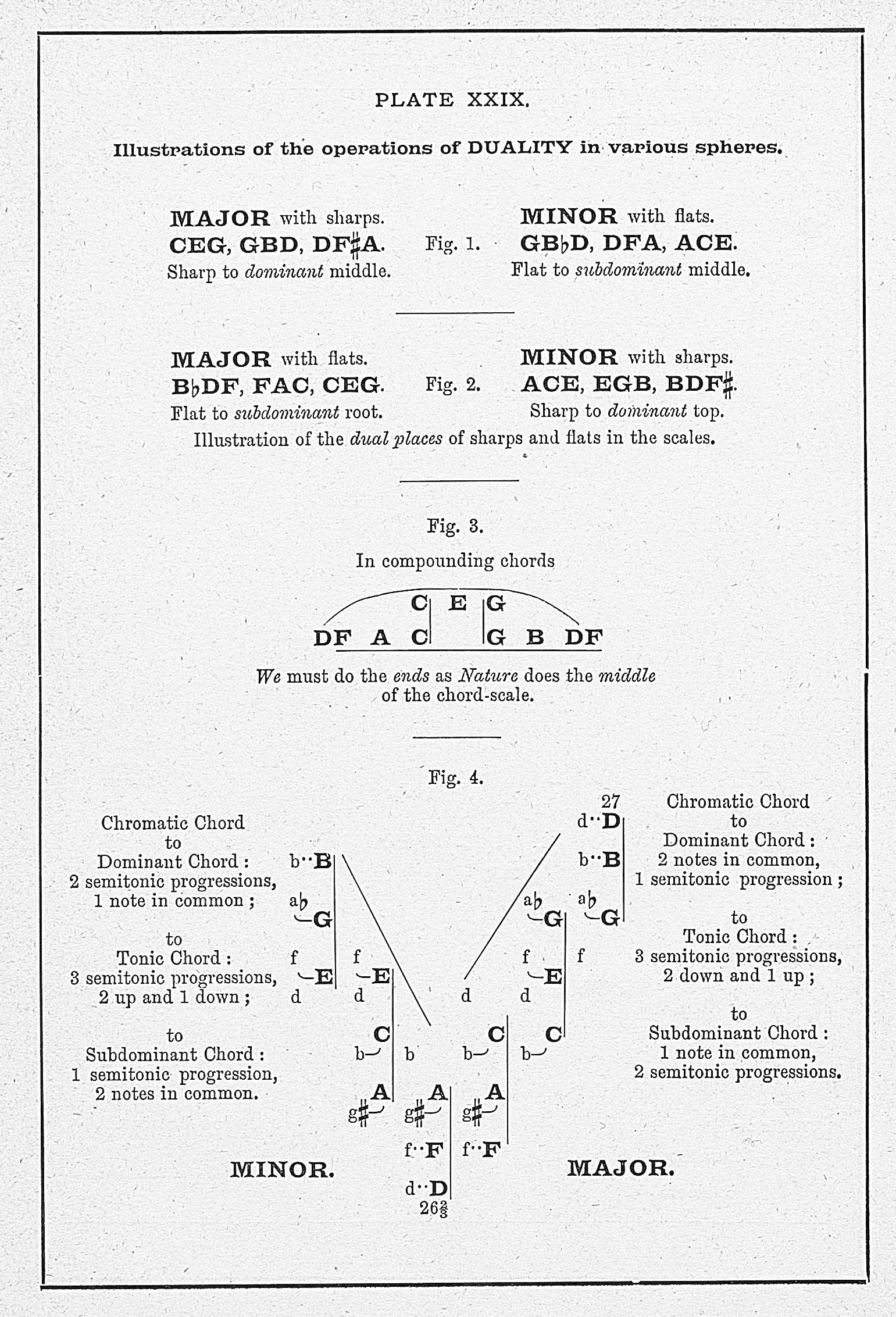

In Fig. 1 is shown the way in which duality arranges the new sharp in the majors to the middle of the dominant, and the new flat to the middle of the subdominant in the minors, all through the six scales done in flats and sharps. The flat goes to the root of the subdominant and the sharp to the top of the dominant in the other six, as in Fig. 2. This is the invariable way that the new sharps and flats are responsively added all through the system. [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 120]

Fig. 3 illustrates the way Nature teaches us by example how to compound so as to enable chords that are separated by the intervention of others to pass to each other. In the middle of the chord scale Nature gives the root of the one chord to the top of the other, and the top of the one to the root of the other; in compounding we are taught by this example to do the same, and the top of the separated dominant is given to the root of the [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 120]

distant subdominant, and the root of the separated subdominant is given to the top of the distant dominant. Here also duality holds sway. [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 121]

Fig. 4 is a setting of the minor and the major chord-scales, showing how they stand linked by notes in common in their direct sequence from dominant minor to dominant major. To each of the six chords is placed the first chromatic chord, showing how it resolves in its three-fold manner by 1, 2, and 3 semitonic progressions in each mode, and by 1 and 2 notes in common variously in each mode; and here again the law of duality is seen in its always symmetrical adjustments. Duality, when once clearly and familiarly come into possession of musicians, will be sure to become an operative rule and test-agent in composition. [Scientific Basis and Build of Music, page 121]

See Also